There a variety of strategies to learning kanji. It seems like everyone has a different method they employ, and that they swear by. You might have even heard a few heated debates in your time over what is the best way to study kanji. You could say that there seem to be just as many ways of studying kanji as there are people, and there is a reason for that.

We all learn differently!

There really isn’t a one size fits all to learning kanji. It requires a bit of experimentation and adjusting. And in fact, you might have to use a variety of different strategies if you find yourself struggling to remember kanji or if a particular one is giving you serious headaches. In either case, it is good to know about all the strategies in order to choose for yourself.

In this post, I’d like to go over a few of the main strategies and point out what they can do for you and how to make adjustments so that you fit you the best.

Brute Force

At some point, you have heard of or used the brute force method. This involves basically writing one kanji or a particular kanji compound several times on a drill sheet. A lot of people find this extremely boring and repetitive. It doesn’t exactly sound very appealing does it?

You have to really understand what exactly is going on here. You essentially have two types of memory – declarative memory and procedural memory. Procedural memory is sometimes often considered ‘muscle’ memory as in your muscles somehow have little mini brains remembering things for you. But that is not exactly the case.

Procedural memory is long-term memory that helps you remember, well, procedures. These are motor skills needed to do certain tasks like riding a bike or driving a car. Once you’ve learned these skills, you tend to remember them for a very long time.

When I first moved to Japan, I bought a bike. It had been many years since I rode one, probably a good 5 years at least, maybe more. But, I could ride the bike just fine with a few minor difficulties at first. That memory, despite being dusty and neglected, came back with relative ease. Procedural memory can be quite powerful.

And that is what you are practicing when you brute force write down kanji over and over. You are inscribing the procedure, the exact muscle movements needed to create that kanji. And that is kind of useful. In that way, you don’t have to remember how to write each one stroke by stroke. You can kind of just tell your hand to write it.

However, you are not inscribing meaning or even how to read the kanji when you do this, at least if you are doing it silently to yourself. That is why it can be ineffective. If you say the sound of the kanji repeatedly while thinking of the meaning, you can help encode the meaning and sound, but this isn’t foolproof. It still has issues.

You’ll still have to do regular spaced review in order to master it. And it can get very boring very quick. And in the modern world with smart phones and such, you can actually get away with not being able to write kanji at all.

There are different ways to approach it though. For instance, if you use it as a way to practice mental focus like monks copying scriptures, it can provide two benefits at the same time.

Heisig / Mnemonics

Heisig wrote Remember the Kanji I and changed the way people learned kanji. It contains useful mnemonics and tricks on how to lock in kanji. And there are a number of people that work their way through the entire volume memorizing all 2000+ characters needed to read everyday Japanese (常用漢字, jyouyoukanji).

And learning how to read an entire language before diving into it is a good idea, at least in theory. There are a few folks who have managed this feat in under 100 days! And I believe that this is total possible if you have the grit and determination to get through it. As a matter of fact, you could probably find yourself in a regular pattern of study that would make this actually fun in a way.

However, most people just want to ease into a language, learning a few simple phrases there, a few key words there. I would think that unless you were suddenly assigned to the Tokyo office at your company, you might not be eager to jump head-long into learning all the kanji in one shot.

The Heisig also doesn’t match up well with the JLPT levels. So, if you are looking for the most efficient way to study for each level, this might not be your best match either. You might find the strategies used useful though. Breaking kanji down into radicals and making mnemonics for each one can be quite useful.

The Koohii website has a lot of great useful tools to help you practice with the Heisig method and share mnemonics with other users. Memrise also has a feature where you can select mems (mnemonics) created by other users or create your own.

Absorbing Kanji

Another ‘method’ of learning kanji is to simply absorb through reading, drilling words using kanji, and generally being observant. This is a bit of a lazy method to be honest. And the one I have been using for most of my kanji studying career.

I did start out drilling and making mnemonics for the first 100~300 kanji, but I found mnemonics only helped up to a point. After a while, it just wasn’t working for me, I found that if I drill words with Anki or Memrise using native kanji I was able to recognize kanji pretty easily on my own. The N5 level only covers about 100 kanji, but the vocabulary for that level easily uses more than that. So instead of drilling words in hiragana, I always drilled them in kanji even if that kanji wasn’t on the test.

The result is that I got a lot better at recognizing more difficult kanji. I’m also added by the fact that I am surrounded by kanji every day living in Japan, so this method is obviously not for everyone. And I still have a few holes in my reading that would have gotten patched up if I had actually walked through the steps of actually learning every kanji.

So is this a good method? Well, it is the lazy method. I’ve never really had issues with the kanji section of the test, and don’t have many issues reading day to day stuff. There are a few moments when I mess up the reading of a word, but for most part it works for me.

Key Components

No matter what method you use now or in the future. There are a few things to keep in mind that will dramatically decrease the amount of time you spend studying kanji.

Learn Radicals

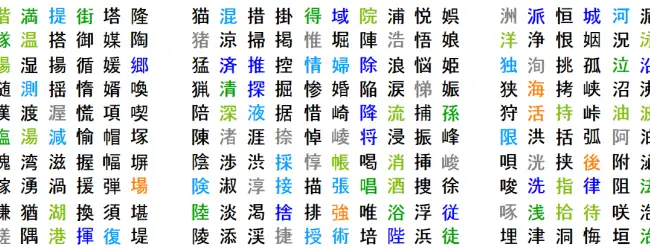

I wrote up an article about radicals a while ago. But in short, radicals are the small little parts that kanji are made out of. They can help breakdown even the largest, most complex kanji into much smaller, more easily remembered parts. It can also help you look up kanji if want to know their readings.

Use Mnemonics

Mnemonics, especially ones that use colorful and creative imagery, are absolutely invaluable for remembering any piece of information. They can be a lot of fun to create and play around with. The crazier and more obscene you can make them the better.

How about you?

How do you study kanji? What was the most effective for you? Let me know in the comments below.

I’m using a combination of “Mnemonics” and “learn via vocab”.

I’m using Genki, Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course, and the “Kanji Study” android app.

I use the Kanji for the Genki vocab for my flashcards for each chapter. I have three cards per note in Anki: E->J, J->E, and Kanji->reading.

I also flag each Kanji I’ve studied via KKLC and a few vocab words for each in KanjiStudy and use that app for writing practice (English->Kanji) and for “Pick the correct Kanji to complete the word” drills.

I’m still working through Genki 1, so I’ll have to wait and see how effective this turns out to be.

It’s certainly possible to learn the Jouyou kanji in 100 days. I did it working full-time in less than half that using the book (RTK) and the kanji.koohii.com website. I had previously studied Japanese (and kanji) many (10+) years ago, so while technically I wasn’t starting from zero, my memory of how to write (or even recognise) kanji had atrophied quite a bit.

I’ll say two things about RTK, that I think are worth bearing in mind.

First, I think that unless you devote a reasonable chunk of time to learning the kanji (let’s just say writing them, because that’s all RTK helps you with) and you follow a systematic method that actually works, you’re liable to hit a wall where adding new kanji to your repertoire is as likely to confuse you on kanji you already “knew” as it is to actually increase the number you know. You basically have to either use something like Heisig’s techniques or be willing to spend a lot of time revisiting old kanji and figuring out how to solidify them while still learning the new stuff.

The plateau effect where you’re not able to effectively add new kanji knowledge is a big demotivating factor. I know that it was for me, even living in Japan and being exposed to kanji everywhere and actually having a reasonably large (~500 kanji) starting set.

The second point is that even after getting through RTK and then getting all your kanji into the 30+-day box on kanji.koohii.com (ie, pretty well installed in your long-term memory), your journey is really only starting. Two sub-points on this:

2a RTK only taught you how to write a character using a single English-language trigger word. You need to learn how to read it, both in isolation (eg, knowing that 証 is ショウ, while 正 could be ショウ or セイ) and when it appears in vocab (including weird stuff like 行方 or 仮令).

2b You need to transition from using a single English-language trigger word to something that makes sense in Japanese. A lot of the RTK keywords are, frankly, not very good. For one thing, they don’t take any account of how frequently each kanji is used, so you get cases like the most basic English word “I” (ie, me) assigned to the kanji 吾, which is very rarely used. That’s only one category of flaw. I could come up with probably a dozen different ones, all of which show that Heisig’s method of assigning a single English keyword to a kanji is suboptimal when you want to move on from merely learning to write to learning to be properly literate.

In summary, point 2b is basically that you will have to relearn everything again after RTK, but this time avoiding all the poor keyword choices. That is, assuming you still want to be able to write, and not just use RTK as a stepping stone to reading ability.

Overall, I did find RTK very useful, but that’s mainly because it helped me overcome the plateau effect I mentioned earlier and effectively let me overcome the first major hurdle to my path to proper literacy in Japanese. Don’t think that it’s the end of the journey, though, and don’t fall into the trap of thinking that that’s the hardest part out of the way. Take it from me, it’s not. Although, that said, I do recommend following RTK, but be sure to follow through and be aware that RTK is really only a crutch or useful tool that you will need to outgrow.

Thanks Dec for taking the time walk us through how to get the most of RTK. I’ve never walked through it so it is good to hear other’s perspectives on it! Thanks for sharing.

Won’t they provide the furigana for some kanji in the JLPT exam? I took a mock test before for N5 and it had furigana.

Yes, there is furigana in the reading section, but in the vocabulary and kanji section at the beginning of the test doesn’t have furigana. You’ll need to learn the readings for that section.